Carter's Grove Archaeological Report, Block 50 Building 3Originally entitled: "The Carter's Grove Museum Site Excavation"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Research Report Series - 1561

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

THE CARTER'S GROVE MUSEUM SITE EXCAVATION

Department of Archaeological Research

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

May 1989

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| List of Figures | ii |

| List of Photographs | iii |

| Acknowledgements | iv |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Previous Work | 3 |

| Methodology | 8 |

| Environmental Setting | 9 |

| The Prehistoric Site | 11 |

| The Historic Site | 20 |

| Conclusions and Recommendations | 31 |

| Bibliography | 33 |

| Appendix I. Description of Prehistorie Artifacts | 36 |

| Appendix II. Additional Excavations | 48 |

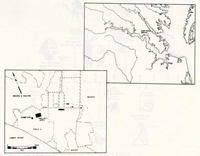

| 1. Site Location | 2 |

| 2. Time Line of Occupations at Carter's Grove | 3 |

| 3. Previous Excavations | 5 |

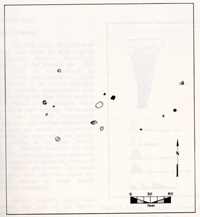

| 4. Plan of Prehistoric Features | 12 |

| 5. Profile of Irregular Shaped Pit | 13 |

| 6. Dog Burial | 15 |

| 7. Shallow Basin Shaped Pit | 16 |

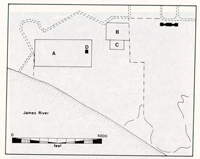

| 8. Plan of Historic Features | 20 |

| 9. Plan and Profile of Pit 4 | 26 |

| 10. Postholes Outside of Structure | 28 |

| 11. Examples of Projectile Points | 41 |

| 12. Historic Features-Septic Area | 50 |

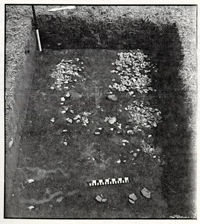

| Shell Midden Excavated by Smith and Cross | 6 |

| The Excavation of the Roasting Pit | 18 |

| Excavation of the Northern Building | 21 |

| The Southern Building | 23 |

| Townshend Vessel Recovered from Roasting Pit | 39 |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Lefty Gregory, Keith Egloff, Paul Peebles, Robert Hunter, Ivor Noël Hume, Vanessa Patrick, Willie Graham, and Dr. James Adavosio for their insight and expertise in association with the interpretation of the museum site. Kim Wagner (graphics), Tamera Mams (photography), Nicola Longsford, and Julie Reilly (conservation) provided the technical excellence experienced throughout the project. And finally, thank you to the entire Department of Archaeological Research field and lab staff for all their hard work.

INTRODUCTION

The Carter's Grove Museum site excavation began in December 1987 and was completed the following June. The proposed construction of a museum to house the Martin's Hundred collection required an investigation of the archaeological remains within the project area. The impacted portion covered 18,500 square feet on a knoll located approximately 1000 feet southwest of the Mansion.

While all Colonial Williamsburg construction activities result in some type of archaeological investigation, the location of the Museum site mandated a comprehensive look at this area. Carter's Grove Plantation has provided archaeologists with a wealth of information about prehistory, early colonial settlements, and 18th-century plantation activities. The proximity of the proposed construction site to Wolstenholme Towne, the possibility of an 18th-century cemetery extending into the project area, and the probability that a prehistoric site would be located on the hill all contributed to the conclusion that full excavation of the area was indeed necessary.

The proposed museum site is located on a knoll approximately 1500 feet north of Wolstenholme Towne. Proximity to the early settlement suggested the possibility of a related activity area on the knoll. While the 1971 survey found no clear evidence of major activity in this area, a series of boundary ditches possibly dating to the 17th century were uncovered nearby. Further, a 17th-century trash pit was discovered in the field between the settlement and the knoll.

The impact of proposed construction on the 18th-century Burwell cemetery, located just to the west of the project area, seemed a more distinct possibility. Two vaults inscribed with the names of Burwell family members survive in the field today. These-markers, along with the recovery of a right parietal bone from of a human skull at the entrance of a groundhog's den near the vaults, clearly suggest the existence of a cemetery on the hill. As with most historic cemeteries, there is a possibility that unmarked graves extend beyond the present boundaries.

Prehistoric activity in the impacted area was also possible, given the relationship of the site to the James River. The typical settlement pattern for the Woodland period is one of large settlements near the "zone of freshwater/saltwater interfaces and along major drainages" (Hunter 1986:46) . The Museum site fits both criteria, and is also located on a elevated terrace, a topographic situation with high potential for prehistoric settlement.

These combined factors required the complete excavation

of the impact area. A preliminary survey in which shovel tests were placed every

twenty feet recovered very little evidence of previous occupation on the site.

As a full excavation later revealed, however, these results only highlight the

shortcomings of current site-identification techniques, as current methods of

site identification seem inadequate for discovering some prehistoric and

17th-century settlements. The 1971 survey and

2

Figure

1. Site Location

shovel testing of the area recovered some material, but

not enough to justify a more thorough investigation at the time. The preliminary

survey the Department of Archaeological Research conducted prior to the

excavation was also unable to locate any indications that full excavation was

necessary. These results appear to indicate a structural flaw in the mechanism

which determines the sites that receive further attention. Shovel testing alone

is inadequate in identifying sites which do not contain heavy concentrations of

cultural material.

Figure

1. Site Location

shovel testing of the area recovered some material, but

not enough to justify a more thorough investigation at the time. The preliminary

survey the Department of Archaeological Research conducted prior to the

excavation was also unable to locate any indications that full excavation was

necessary. These results appear to indicate a structural flaw in the mechanism

which determines the sites that receive further attention. Shovel testing alone

is inadequate in identifying sites which do not contain heavy concentrations of

cultural material.

PREVIOUS WORK

Starting with William Kelso's original survey of Carter's Grove in 1970-71, a series of archaeological investigations have occurred on or near the ridge that will house the Martin's Hundred Museum. These inquiries have been conducted for differing specific reasons, but all have uncovered portions of past occupations on the ridge.

Kelso's intensive survey involved both shovel testing and, when artifacts were recovered, machine stripping of the plowzone to uncover features. He set out to locate outbuildings associated with Carter's Grove Mansion. During this process he uncovered a large number of sites not related to the Mansion, including Martin's Hundred. One of the sites identified was the prehistoric site on the western end of the ridge in Field 9. This Woodland site included both intact cultural stratigraphy (CGER 992 and CGER 993) and an ossuary (CGER 1015), a large pit containing secondary burials (Kelso 1971:71). While these activity areas were uncovered by machine removal of the plowzone, the site was recorded but not tested. No significant historic features were uncovered on the ridge, but a series of boundary ditches were located to the south.

4After Kelso's survey revealed the presence of a prehistoric site of some significance, Dr. Norman Barka of the College of William and Mary was contacted in order to test and date the Indian site on the ridge. In April 1971, Barka examined both the ossuary and midden, plus an area to the east of the 18th-century Burwell cemetery. His report concludes that the undisturbed Indian shell midden probably represents the main living area of the Indian population (Kelso 1971:72). The area of the ossuary uncovered by Kelso was not excavated, but was examined. A six-by-six foot square was uncovered, revealing nine or ten closely-spaced bundle burials. This feature was interpreted as a possible large ossuary dating from A.D. 350-1600 (Kelso 1971:71). While the testing of the area east of the 18th-century graves revealed no prehistoric layers or features, Barka did uncover several late 17th- or early 18th-century features near the cemetery. These features were mapped but not excavated and are located just west of the current project area. These maps and notes have since been misplaced, but the presence of datable artifacts may indicate that the features were part of a domestic activity area.

In May 1979 the Virginia Research Center for Archaeology (VCRA) conducted an investigation on the ridge in Field 9. At the request of Ivor Noël Hume, the VRCA under the direction of Keith Bott examined the prehistoric site in order to determine its relationship to the Martin's Hundred site. Mr. Noël Hume argued that the founders of Martin's Hundred settlement chose this location to settle because it had previously been cleared by Native Americans. To prove this contention, a more precise date of the prehistoric occupation was needed. Four test units were excavated and the report concluded that the site displayed vertical stratigraphy, dating from Middle to Late Woodland. The predominant diagnostic artifact for the Middle Woodland occupation was a pottery type known as Mockley ware, generally dated between 200 and 900 A.D. (Egloff and Potter 1982:103). The Late Woodland occupation was identified by the presence of Townsend pottery, generally dated between 900 and 1600 A.D. (Egloff and Potter 1982:107). The report concludes that the concentrations of shell midden were intermittently spaced throughout the site (Bott 1979:43) and may indicate either sparse and periodic occupation or else site disturbance. The excavation was unable to reveal the relationship between the Indian occupation and Martin's Hundred. Although the VRCA was able to identify and date the Late Woodland occupation, the long period of Townsend ware production hampered efforts to precisely date the latest period of Indian occupation.

An area of intact shell midden was uncovered during

both Barka's and Bott's excavations. The midden was identified as the "main

living area" by Barka in 1971, and included pottery from both the Middle

and Late Woodland occupations. Cultural stratigraphy was recorded in two of the

test units, and the midden was divided into "midden" and "lower

midden" layers. The "midden" layer contained over 80 percent of

the later ceramics--in this case Townsend ware--in both units. In turn the

"lower midden" layer contained over 80 percent of the earlier Mockley

ceramics identified in the same unit. Along with pottery and lithics, faunal

material including deer, sturgeon, and turtle was recovered. Large-scale shovel

testing uncovered three areas of shell concentrations. This intermittent nature

of the midden was due to either

5

Figure

3. Previous Excavations

sparse occupation or disturbance of the midden.

Figure

3. Previous Excavations

sparse occupation or disturbance of the midden.

Two excavations were conducted during the 1980's. In

1985 Nate Smith and Mary Zylowski of Colonial Williamsburg's Office of

Archaeological Excavation tested the construction site for the Martin's Hundred

Overlook. While monitoring, a prehistoric shell-fîlled feature was encountered

and subsequently excavated. No datable artifacts were recovered. Eight

five-by-five foot squares were later opened in an area around the Overlook

scheduled for landscaping activity. These squares

6

Shell

Midden Excavated by Smith and Cross.

uncovered evidence of three historic boundary ditches.

The plow zone contained Middle Woodland pottery, Late Woodland pottery, and two

projectile points dating to the Middle Archaic, but no intact prehistoric

features were uncovered.

Shell

Midden Excavated by Smith and Cross.

uncovered evidence of three historic boundary ditches.

The plow zone contained Middle Woodland pottery, Late Woodland pottery, and two

projectile points dating to the Middle Archaic, but no intact prehistoric

features were uncovered.

In 1986 Nate Smith conducted an extensive testing project north of the Overlook site in preparation for museum construction. A concentration of oyster shell identified as a midden deposit was uncovered and partially excavated. Complete excavation of the area never occurred. This smaller shell midden contained intact cultural layers. The uppermost was identified as "upper fill," and was characterized by a heavy concentration of oyster shell in a dark brown sand. This layer sealed a brown sand that contained less oyster shell. The two layers contained animal bone, oyster and clam shells, and equal densities of Mockley ware. One quarter of the midden was 7 completely excavated, with no Late Woodland component discovered (Smith and Cross 1986). A historic boundary ditch was also uncovered. The proposed site of the museum was later changed from this area to its present location.

Some common themes emerge from a consideration of these excavations. Intact prehistoric stratigraphy evidently survived the plow in at least two areas of the ridge. Further, the entire ridge appears to have been used by both Indians and colonists, with Middle Woodland artifacts recovered across the entire ridge; the Late Woodland activity was concentrated to the west of the Burwell vaults; and the historic activity centered to the east of the cemetery. While cultural layers associated with historic activity have yet to be located, historic features appear to have survived throughout the ridge. The results of these past investigations suggest that prehistoric activities began in the Archaic period, were restarted in the Middle Woodland, and continued until the Late Woodland period. Historic activities seem to date to the late 17th or early 18th century, with the exception of the boundary ditches found throughout the ridge. No tightly datable artifacts have been recovered from any of the ditches, but the presence of hand-wrought nails suggest a colonial construction date.

METHODOLOGY

The grid system established during the 1970 survey of Carter's Grove was employed for the excavation at the Museum site. This particular system separates the area around the mansion into a series of 200-, 50-, and finally 10-foot divisions. Each ten-foot unit was given a unique Carter's Grove Excavation Register (CGER) number, and each layer/feature was assigned a letter for recording and laboratory purposes.

Before mechanical stripping of the plowzone began, a preliminary survey was conducted to insure that the machine activity would not adversely affect surviving features. Shovel tests were placed every twenty feet, and the fill was hand-troweled to recover artifacts. Results indicated that any damage caused by machine removal to surviving features would be minimal.

The impact area of the museum was calculated and the plowzone was mechanically removed from this area. When it became apparent that expansion of the area of investigation would be necessary, additional plowzone was removed. A total of 139 ten-by-ten foot squares were eventually uncovered. All exposed features were then mapped, sectioned, recorded, and removed, with fill being screened through one-quarter inch mesh. Soil samples were taken from prehistoric features to be use for flotation and/or chemical analysis. All elevations were recorded from a single transit station. Artifacts from both the prehistoric hearth and the large historic pits in the southern building were piece-plotted.

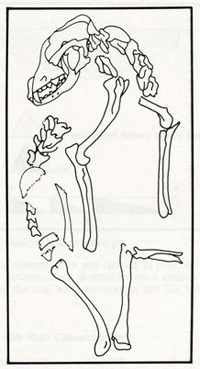

The prehistoric dog burial required special treatment from the conservation lab. The pit was sectioned east-west, with the southern half being removed first. The fill was excavated in arbitrary 0.2 foot levels until a large amount of bone appeared. At that point a decision was made to pedestal the bones. The northern half of the pit was then removed, with all areas of bone being pedestaled. The pedestaled area was then cut at the subsoil level, allowed to freeze naturally, and was removed to the Department of Conservation of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

In the lab, the pedestal was thawed at room temperature for two days. Using dental picks, fine brushes, and atomized water the excavation process continued. Ethanol was applied to all portions of exposed bone to aid in soil removal, and a polymerized vinyl compound was used for consolidation. Each bone was charted, measured, and removed. Undemeath the bones an area of smooth grey soil was noted, capped by organic soil containing linear ribbed impressions, later identified as open twined woven textile impressions. These marks covered over half of the soil underlying the skeleton and are currently being conserved.

ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING

Carter's Grove plantation comprises approximately 800 acres situated on the north bank of the James River, between Grice's Run (which borders the property to the southeast) and Wareham's Run, a little over 1.1 miles to the northwest. Carter's Grove centers on a neck of high ground, separated by ravines and swamps-characteristic of land well-suited for agricultural activity. The distinct high-ground topographic feature known as the Kingsmill scarp is an ancient beach head, trending east-west and fronting onto the James River. The area from this high ground gently slopes to an ancient river terrace approximately thirty feet above sea levei. Most of the direct river frontage from that point consists of steep, eroded bluffs (see below).

The excavation took place in an open field approximately 307.6 meters southwest of the mansion and 18.4 meters west of the current interpretive pavilion for Wolstenholme Towne, atop the Kingsmill scarp. This particular area appears to have been mostly open farmland, cultivated over the past several hundred years. Little or no agricultural activity is being conducted in this area at present. Most of the area surrounding the site is covered by mixed deciduous and conifer forests of loblolly pine, oak, spruce, fir, cedar and holly, with an understory of dense honeysuckle, various ivies, and greenbriar. To the south is the James River.

The climate during the course of excavation was typical of the seasonal changes common to the east-central portion of the Virginia Coastal Plain, where the average winter temperature is 41 degrees Fahrenheit and the average spring/summer temperature 76 degrees. The average relative humidity ranged from 80% or less in the morning to 60% or less in the afternoon. Prevailing winds were generally strong (over fifteen mph), mostly originating from the southwest.

Erosion appears to have been a significant process in the development of the present-day topography, with the northern and southern slopes of the scarp receiving the greatest impact. Coupled with annual plowing from preceding years, archaeological features along these slopes were either partially destroyed (with only the bottom portions exposed) or, in some instances, completely obliterated. Natural erosion, particularly in areas along rivers and streams, appears more substantial than in other regions. Plowed fields left exposed to wind and water processes were generally devastated by these erosional elements. The severe storms characteristic of the James River area are probably the most significant natural earth-moving factors.

Specific Morphology

The topography of southeastern Virginia is characterized by a succession of coastal and riverine scarps and terraces. The terraces are emergent plains formed under stream estuarine, bay, swamp and marsh conditions during the late Pliocene and Pleistocene; they decrease in elevation seaward and toward the major rivers. The scarps, which were cut by shoreline erosion, maintain remarkably uniform elevations 10 all along the Atlantic Coastal Plain (Cooke 1931; Cooke et al. in press). The number, origin and age of the terraces has been the subject of much controversy (Cooke 1931; Flint 1940; Oaks and Coch 1973).

The Surry scarp (Flint 1940), which passes north-south through Williamsburg, marks the boundary between the Middle and Lower Coastal Plain. The toe of the scarp is at an elevation of about 29 meters and is cut into Pliocene-age strata. The Lackey plain (Johnson 1972) extends from the Surry scarp eastward to the Ruthville scarp and trends northeast-southwest across the innermost Lower Coastal Plain. The plain, which reaches its maximum elevation of 27 meters against the Surry scarp, slopes eastward to about 25 meters at the crest of the Ruthville scarp. On the York-James Peninsula and near major rivers elsewhere, the plain is extensively dissected. The Surry scarp was a fastland beach and the Lackey plain was covered by open bay when the Windsor Formation was being deposited during the Early Pleistocene.

A low, subdued scarp--the Ruthville--forms the boundary between the higher plains in southeastern Virginia and the Grove plain. The Grove plain, on which Carter's Grove mansion is constructed, extends from the base of the Ruthville scarp seaward to the Lee Hall or lower scarps and varies in elevation from 22 to 24 meters. The Grove plain was formed as an estuarine-bay plain during the Early Pleistocene.

The Kingsmill scarp is the most continuous and, in many places, the most prominent scarp along major rivers in the Coastal Plain. It trends east-west and forms the declivity between the upland upon which the Carters Grove mansion is built and the flat below. The base of the scarp ranges in elevation from 13 to 14 meters. The Huntington flat (Coch 1971) is bounded landward by the Kingsmill scarp and by the James River at Carter's Grove, and ranges in elevation from about 10.5 to 14 meters. The plain was formed during the late Middle Pleistocene by the ancestral James River estuary and adjoining ancestral Chesapeake Bay. Severe wind and water erosion along the James River created the existing bluffs and beach. An underlying ancient bed of water-deposited chert and quartzite cobbles is currently eroding from the bluffs. The proximity of this layer to the site suggests this was a primary source of lithic materials for toolmaking by the Indians.

THE PREHISTORIC SITE

Three time periods of prehistoric occupation are evident on the terrace at Carter's Grove. Each period contains what seem to more than one periodic occupation of the area. Occupation began in the Archaic Period, with two projectile points being the only surviving evidence of settlement. The second occupation, and that which represents most of the activity uncovered during this excavation, took place during the Middle Woodland period. Finally, the last prehistoric occupation took place during the Late Woodland period. While not extensively represented at this excavation, the features dating to this period offer the most insight into the past.

As erosion and plowing have removed or disturbed the original occupational surfaces or any midden deposits which may have existed, prehistoric activity is represented solely by those portions of discrete intrusive features which extend below the plowzone. Fortunately, in areas adjacent to the ridge, some cultural layers have endured both the plow and nature. In the project area artifacts from these destroyed layers and features were recovered in the plowzone.

Four types of prehistoric features have been identified at the Museum site, each representing a distinct activity. A description, time period, and function (if possible) will be given to each feature type. The features, dating from the Woodland period, illustrate that at least two different settlements were present. Based on these features it appears that the first Woodland occupation represents one or more seasonal encampments in the Middle Woodland period (A.D. 200-900). The site was later inhabited in the Late Woodland period (A.D. 1000-1600) and may represent a peripheral activity area relating to a small semi-permanent settlement located nearby. Both of these occupations extend outside of the project area.

Archaic

While no features can be designated to the Archaic period, the presence of two Archaic projectile points indicates that an Archaic settlement once existed on the ridge. The Archaic period, which started around 6500 B.C., continued until the introduction of pottery sometime around 1200 B.C. Climatic changes resulted in a change in local exploitable resources which in turn allowed more general foraging/hunter activities during this period. The environment was characterized by a widespread warming trend and a rise in the amount of rainfall, which fostered the development of deciduous forests. Sea level was rising at a slow rate and food resources became more diverse. Plants and animal resources were comparable to those today, with deer and turkey being the primary game. The Archaic period was also characterized by an expanding variety of stone and bone tools, a increased diversity of site types, and a larger number of sites reflecting a growth in population.

12 Figure

4. Plan of Prehistoric Features.

Figure

4. Plan of Prehistoric Features.

No stratigraphically-intact evidence had survived at the site, but the recovery of a Le Croy (Early Archaic) and a Morrow Mountain II projectile point (Middle Archaic period) recovered from the plowzone suggested occupations had once been occasionally been established there. Local prehistorian Robert Hunter points out that most:

. . . local Archaic occupations are reflected by the presence of diagnostic points found in disturbed context in association with later prehistoric materials on a large riverine sites ... The most conimon local Archaic site type is a large base camp usually found near a raw material source (Hunter 1986:46).The Archaic occupation at the Museum site could in no way be characterized as a 13 "large base camp".

Middle Woodland

The wide spread distribution of Mockley ware across the ridge suggests overlapping Middle Woodland occupations at the Museum site. This time period is characterized by exploitation of marine resources, a more sedentary way of life, and an expansion of trade networks. Exploitation of local shellfish during this time period resulted in the creation of shell middens, where oyster shells were dumped. These sites were often occupied intermittently through time and artifacts recovered at these sites are usually multi-purpose, indicating that more than one activity was occurring at the sites (Hunter 1986:57). Mockley ware was the only Middle Woodland pottery type recovered. Small quantities of quartzite, jasper, and quartz flakes, along with fire-cracked rock, were also recovered which are probably related to these Middle Woodland occupations.

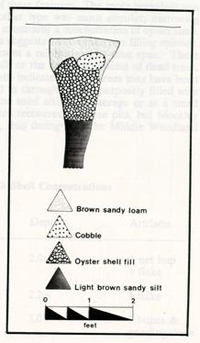

Figure

5. Profile of Irregular Shaped Pit.

Figure

5. Profile of Irregular Shaped Pit.

Several projectile points were recovered that date to the Middle Woodland Period. These points identified as Rossville type date from ca. 500 B.C. to A.D. 400. The points were made of jasper and quartzite and were recovered in an association with a concentration of jasper and quartzite flakes and cores at the southern central portion of the excavation. This concentration may represent a discrete activity area used for the production of the Rossville points. The cobbles used for this production are very similar to those found eroding out of the bank of the James River directly south of the site.

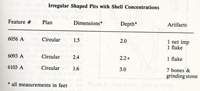

Irregularly-shaped Pits

Several irregularly-shaped features were located throughout the site. While varying in size, all had sloping sides which tapered towards the bottom. The holes contained charred wood, oyster and fossil shell, burned clay, cobbles, animal bone, and pottery.

14There were at least two varieties of these features. The more prevalent was irregular in plan and section, while the other type was more circular, narrowing gradually towards the bottom of the pit and containing a concentration of oyster shell. Discernable layers in some of these features suggested more than one filling episode. All of the filling activities seemed to represent a relatively short time span. These features were probably the result of tree falls or the decaying process of dead trees. The burned clay and charred wood in the pits indicate that the trees may have been burned. These holes may have been filled in through silting, purposely filled with waste from the site, or partially filled-in and used either for storage or as a small cooking pit. No diagnostic stone tools were recovered in these pits, but Mockley ware was recovered in one of the features, thus dating it to the Middle Woodland (200-900 A.D.).

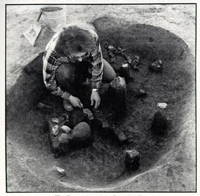

Dog Burial

A Middle Woodland dog burial (CGER 6032A) was uncovered in the southwestern quadrant of the site. The pit was an irregular oval shape with vertical sides and a flat smooth bottom, measuring 3.0 feet east-west, 2.4 feet north-south, and 1.0 feet deep. The fill was a dark brown sandy loam with charcoal flecking. The pit contained an entire articulated dog skeleton. While plowing had removed part of the pelvic area, the rest of the animal was intact. Complete analysis of the dog remains will be completed at a future date.

Dogs were used by Woodland Indians as guardians, for companionship, for food, and sometimes for ceremonial purposes during the Late Woodland period (Butler and Hadlock 1949). Over 106 dogs have been excavated at the Hatch site 15 located up the James River about 30 miles (Gregory, personal communication). Some of these were buried in primary internments like the dog recovered at Carter's Grove, and lacked caudal vertebrae, suggesting that they were skinned but not eaten. Removal of the pelvic region of the Carter's Grove dog by plowing made it impossible to determine if it had been skinned. The fact that the dog skeleton was articulated, however, indicated that it was not used for food. Occasionally the dogs at the Hatch site seem to have been used ceremonially, but no such evidence exists for the dog at the Museum site.

The soil beneath the dog bore the impression of a woven textile, extending the entire length of the pit. Identified as a open-twined textile by Dr. James D. Adavasio of the University of Pittsburgh, this impression may represent the remains of a mat or woven sack. No evidence of the impression was found above the dog, but it is unlikely that such an impression could have survived if it existed. The impression is eurrently being conserved in order to conduct a more extensive analysis.

Figure

6. Dog burial (Not to Scale)

Figure

6. Dog burial (Not to Scale)

Other artifacts recovered from the burial pit include oyster shell fragments, Mockley ware and quartz flakes. Based on the homogeneous composition of the fill, the shape of the pit, and the presence of the articulated dog it appears that the burial was intentional.

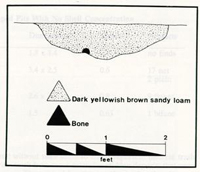

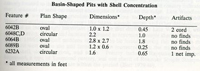

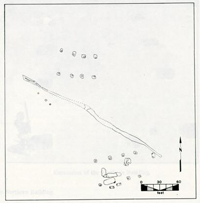

Shallow Basin-Shaped Pits

Several shallow circular Middle Woodland pits were uncovered at the Museum site. The pits ranged in size form 1.0 to 3.4 feet in length with sloping sides and flat bottoms. The features occurred across the top of the ridge with no apparent pattern. A similar feature was uncovered during the construction of the Overlook 16 structure in 1985.

Figure

7. Shallow basin shaped pit.

Figure

7. Shallow basin shaped pit.

The pits can be separated into two different categories based on presence or absence of a oyster shell concentration. The features with the shell concentration fill was made up of two distinct layers. The bottom fill layer was a light brown loamy sand with some charcoal flecking. Artifacts scatters were light and included oyster and fossil shell, fire-cracked rock, flakes, and Mockley ware. The upper layer consisted of a concentration of oyster shell in a dark brown sandy loam. This concentration was circular in plan and less than one foot in diameter. The shell concentrations themselves were shallow and basin-shaped (0.1-0.2 feet deep). Some charcoal was recovered in this fill, but the major artifact group was oyster shell.

Basin-Shaped

Pits with Shell concentration

Basin-Shaped

Pits with Shell concentration

The pits with no shell present contained only a single layer which was very similar to the bottom layer of the shell pits. It too was a light brown loamy sand with some charcoal flecking. Once again a light artifact scatter was noted.

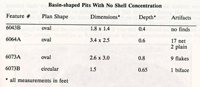

17 Basin-shaped

Pits With No Shell Concentration

Basin-shaped

Pits With No Shell Concentration

Both the pits with and without shell seem to either represent discrete trash deposits or possible incorporate trash from more extensive midden deposits that were destroyed by plowing and erosion. The original function is unknown but the pits were dug intentionally.

Late Woodland

The Late Woodland occupation is represented by features, including the ossuary located to the west of the Museum site. The presence of the ossuary indicates that a seasonal or semi-permanent encampment existed on the ridge. Late Woodland settlements were largely agricultural and therefore more sedentary than Middle Woodland settlements. While crops like beans, squash, maize, and other domesticates provided an increasingly important part of the diet during the Late Woodland, wild plant gathering, fishing, and hunting continued to represent a major share of foodways (Hunter 1986:61). Shell middens continued to be formed during this period to the north and west of the site and faunal remains recovered from the middens include oyster shell, deer, sturgeon, and turtle. Pottery included Rappahannock Fabric Impressed, a type of Townsend pottery, and one sherd of Roanoke Simple Stamped ware, which was produced late within the period (Bott 1979:40).

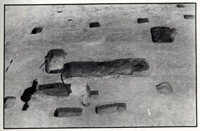

The Hearth or Roasting Pit

A large oval-shaped pit (CGER 6069A) was uncovered in the center of the project area on the crest of the ridge. The pit was filled with a very dark brown sandy loam with a heavy distribution of charred wood. The pit was 6 feet long, 5 feet wide, and 1.4 feet of fill had survived under the plowzone. The feature was lined with fire-cracked rocks and had slightly sloping sides and a flat bottom. The fire-cracked rock 18 mended back together to form large cobbles, indicating that whole cobbles were placed in the pit--probably to diffuse heat--and had shattered during the roasting process. In the center of the bottom was a small pit (CGER 6069C), 1.5 feet long and 1.0 wide. It was 0.3 feet deep and also had a flat bottom. The small pit was filled with charred wood and the surrounding natural clay was discolored red as a result of a fire. The pottery, identified as Rappahannock Incised, crossmended between the small pit and the layers of the larger pit. The large pit contained pottery, charred wood, oyster shell, animal bone, and flakes. This feature was used either as a hearth or roasting pit. Some of the charred bone recovered was identified as large mammal (possibly deer), duck, and snapping turtle. The discoloration of the natural clay indicates that the smail pit originally contained the fire used for cooking. No structural remains were found in association with the pit, indicating that it was an external feature.

Carbon Dating

The analysis of the radiocarbon samples taken from the roasting pit was performed by Beta Analytic Inc. of Florida. Two samples were taken, one from the center of the pit and the other from the small fire pit found in the floor of the large pit. The C-14 age was 540 (+/- 90) B.P. for the sample from the center of the large pit and 670 (+/- 70) B.P. for the small fire pit. These dates are considered to be statistically inseparable.

THE HISTORIC SITE

Several historic features were uncovered and excavated during the Museum site project. Unfortunately no tightly datable artifacts were recovered from either activity area, making the period of occupation somewhat ambiguous.

The historic component consisted of two large

structures, a boundary ditch, and its accompanying fenceline. Each of the

buildings was located on opposite slopes of the knoll, with the ditch and fence

located between them. Artifacts recovered from this area indicate that all

activity was from the colonial period, probably late 17th or

Figure 8.

Plan of Historic Features.

21

early 18th century. Nail fragments, a few pipestems,

animal bone, unglazed coarseware, gun flint fragments, lead shot, and a few

pieces of pipe bowl were the only surviving historic artifacts. This scarcity of

artifacts makes concise dating of the historic occupation difficult.

Figure 8.

Plan of Historic Features.

21

early 18th century. Nail fragments, a few pipestems,

animal bone, unglazed coarseware, gun flint fragments, lead shot, and a few

pieces of pipe bowl were the only surviving historic artifacts. This scarcity of

artifacts makes concise dating of the historic occupation difficult.

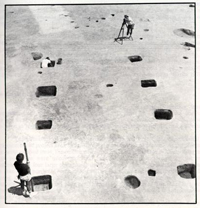

Excavation of the Northern Building.

Excavation of the Northern Building.

The Northern Building

The structure located on the northern slope of the knoll was represented by eight postholes (four to a side), all with postmolds. This structure measured approximately 30 feet along its east-west axis and 15 feet along its north-south axis. The squarish postholes, each measuring 2.5 to 3.0 feet across, were between 1.4 and 22 1.9 feet deep. The holes were filled with a redeposited sandy clay subsoil with very little loam. The postmolds were roughly circular with diameters ranging from 0.7 to 0.8 feet. All intruded subsoil 0.1 feet deeper than the associated postholes. The molds consisted of a brown loam fill with light to heavy charcoal flecking. This suggests that the posts may have been initially burned in order to increase their lifespan. No indication of charcoal was found in the posthole fill. The irregular impressions left by the postmolds suggested that the posts were not hewn before being placed in the ground. No evidence of a fireplace was found, nor were any related features uncovered near the structure. This plus the lack of artifacts (only handwrought nails were recovered), indicates that the building was probably a barn.

David Halstead, in Barn Plans and Outbuildings, states that barns were most often joined-timber framed and were usually rectangular in plan. Barns were usually triparate, with a central threshing floor with flanking mows and mangers. He states "if possible the barn should be located on a rise of ground..." (Halstead 1883:) . A similar structure was excavated at George Washington National Birthplace in Westmoreland County and identified as a barn. This eight post structure was 30 by 20 feet, contained very few artifacts, and bad no associated features (Barka 1978).

The Southern Building

While the southern building was by far the most interesting feature encountered during the excavation, it was also the most frustrating. Four postholes in a line were uncovered at the southern edge of the excavation. The postholes were too large to represent a fenceline and probably represented one side of a structure.

The possibility of a building partially within the project area necessitated the expansion of the project area and machine removal of the plowzone. As the plowzone was being scraped away, the outline of a structure quickly became evident. Four more large postholes were uncovered, and inside the rectangle formed by the eight postholes were four large rectangular soil stains. As excavators scraped and cleaned the area more postholes were uncovered to the south and the east of the building. During the next two months the building was completely excavated, revealing a structure that had obviously been used for some length of time. The other fact, noted painfully by the excavation crew, was that the features making up this structure were virtually devoid of artifacts.

The earthfast building was made up of eight structural

postholes. On each side were located four postholes spaced ten to eleven feet

apart with the building measuring 30 feet along the east-west axis and 20 feet

along the north-south axis. The squarish postholes were 2.0 to 2.5 feet across.

The location of the building on the southern slope of the knoll resulted in more

damage (through erosion and plowing) to the southern line of postholes than the

northern line. Posthole depth on the southern side of the building averaged only

0.7 feet in depth, whereas on the northern side postholes survived to an average

of 1.3 feet below subsoil. The posthole fill consisted of redeposited orange

sandy clay fill, while the only artifacts recovered were nail fragments. The

postmolds were roughly circular, with diameters ranging from 0.6

23

The Southern Building.

to 0.8 feet. These postmolds, like those of the other

building, intruded subsoil deeper than their surrounding postholes. The fill of

the postmolds consisted of a medium brown sandy loam fill with no charcoal

flecking. No datable artifacts were recovered from either the postholes or the

postmolds. One of the southern postholes (CGER 6162A) had been repaired or

replaced.

The Southern Building.

to 0.8 feet. These postmolds, like those of the other

building, intruded subsoil deeper than their surrounding postholes. The fill of

the postmolds consisted of a medium brown sandy loam fill with no charcoal

flecking. No datable artifacts were recovered from either the postholes or the

postmolds. One of the southern postholes (CGER 6162A) had been repaired or

replaced.

Inside the building were five rectangular pits. The presence of these pits suggests that the building did not have a wooden floor. The pits varied in size and shape but did display some similarities. All five were rectangular in shape. Four pits seem to have been partially silted-in with the remainder of each pit intentionally filled. The pits were flat-sided and had flat bottoms. Four had been intruded by rodent burrowing.

Unfortunately all five pits contained only a very light scatter of artifacts. The artifacts recovered (pipe stems and bowls, lead shot, gun flint fragments, and nail fragments) suggest a date of either late 17th or early 18th century. One pit intrudes another suggesting that the building was used over a relatively long period of time and that the pits were not all contemporaneous. While three of the pits have a simple filling sequence, the other two have a surprisingly complex sequence. A short description of each pit and its fill progression is as follows: 24

| PIT | SIZE (in ft.) | LOCATION | RELATIONSHIP | FILL SEQ | ARTIFACTS | SPECIAL FEATURES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 6 x 3.5 1.3 deep | Western end | Cuts pit #5 | Purposeful Fill | Nail frags. Lead shot Grey flint | Cut by 2 postholes after pit filled in |

| #2 | 5.5 x 4.2 3.0 deep | Northeast quadrant | None | Partially silted Purposeful fill | Nail frags. Lead shot Grey flint | Very disturbed by groundhogs |

| #3 | 11.5 x 4.6 3.0 deep | Eastern central | Cuts pit 5 | Partially silted Purposeful fill | Nail frags. Grey flint Pipe stem | Very disturbed by groundhogs |

| #4 | 9.6 x 4.3 1.3 to 2.7 | Southwest corner deep | Cuts structural posthole | Partially silted Purposeful fill | Coarseware Pipe stem/bowl Over 50 nails | Remnants of wooden structure left in pit |

| #5 | 17 x 2.5 3.0 deep | Eastern central | May be part of #3 Cut by #1 | Partially silted Purposeful fill | No historic artifacts | Possibly part of #3 or may be earlier pit |

Pit 1

Pit 1 (CGER 6164A), located in the western end of the building, was 6.0 feet from both the north and southern walls of the building. This was the smallest and shallowest of the pits. Its dimensions were roughly 6.0 feet north-south, 3.5 feet eastwest, and 1.3 feet deep. This pit was filled all at once with a mottled gray compact sandy loam. Nail fragments, lead shot, and grey gunflint fragments were the only artifacts recovered. The artifacts were piece-plotted, but no pattern was apparent.

The southern end of Pit 1 intruded another pit (Pit 5). This overlap indicates that not all of the pits existed at the same time, and the building was therefore in use for an extended period of time. Sometime after Pit 1 was filled in, two postholes of unknown function were dug where the pit had been. No artifacts were recovered from these holes, but both contained small rectangular postmolds. The square holes measured 1.3 feet across and cut through Pit 1 into subsoil. The molds, spaced 3.4 feet apart measured 0.4 feet east-west and 0.6 feet north-south.

Pit 2

Pit 2 (CGER 6164A) was the squarest and deepest of the pits. It was the only pit located in the northeastern quadrant of the building. The pit was intruded by major groundhog burrowing. It measured 5.5 feet north-south and 4.2 feet east-west.

Over three feet of Pit 2 had survived, making it the deepest of the features. The pit was partially silted-in with an assortment of different colored sands and sandy clays. Silting was 0.8 feet deep across the pit bottom. Sealing this silt was a purposely-placed compact orange sandy clay fill. Artifacts recovered included a grey gunflint fragment, one piece of lead shot, and several nail fragments. No pattern for the nail distribution was determined.

Pit 3

Pit 3 (CGER 6163C), located in the eastern central portion of the structure, was also heavily damaged by burrowing. The pit measured 11.5 feet east-west, 4.6 feet north-south, and 3.0 feet deep. This feature also intruded Pit 5, but had no stratigraphic relationship to Pit 1. Like Pit 2, Pit 3 was partially silted with a sandy silt fill. This pit was also partially silted-in with a sandy silt fill, which was 1.0 feet deep. Sealing this fill was a mottled brown sandy loam layer purposefully deposited. Artifacts recovered from this pit include a pipe stem, pipe bowl, nails, and a fragment of grey flint.

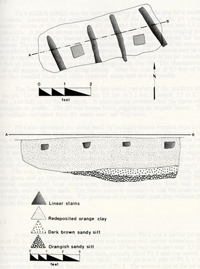

26Pit 4

Pit 4 (CGER 6164D) was the most interesting of all of the pits for a number of reasons. Located in the southwestern corner of the building, this pit actually extended outside of the structure. The pit measured 9.6 feet east-west and 4.3 feet north-south. It had an uneven bottom, with the depth of the feature ranging from 1.3 to 2.7 feet deep. The feature extended to the south slightly beyond the main structure. The intrusion of this pit into a structural posthole suggests that the structure was in place before the pit was dug. The extension outside of the structure may be the result of repairs to the southern wall of the building. The bottom of the pit contained 0.9 feet of silted soil sealed by a mottled orange sandy clay fill. The characteristics of this fill suggest a purposeful filling activity. After the removal of 0.3 feet of this layer four parallel linear soil stains appeared along with two postmolds.

The linear stains ran north-south and ended just short of the northern edge of the pit. The stains ranged in size from 2.8 feet to 3.1 feet in length, 0.5 to 0.7 in width, and 0.25 to 0.4 feet in depth. A cross-section revealed that the stains were rectangular in profile. The fill was brown loam, suggesting an organic source. The only artifacts recovered from the stains were nail fragments.

Pit 4 also contained two stains made by vertically-placed wooden posts in the center of the pit. The square postmolds measured 0.75 feet across and were 1.3 feet deep, with the top appearing at the same level as the linear stains. No postholes were associated with the postmolds, suggesting that the posts were placed while the pit was still in use. The fact that the molds sat on top of the silt-deposited layers suggests that the wooden structure located in the pit was built after the pit was dug and had partially silted-in. These posts were part of the same structural activity that made up slots. The only artifacts recovered from these postmolds were twelve nails, wine bottle glass, and an imported pipe bowl fragment. Artifacts recovered from Pit 4 included unidentified local coarseware, imported tobacco pipe bowl and stem fragments, and over fifty nails. The linear stains in association with the posts seem to be part of a storage structure. Ibe presence of the vertical posts may indicate that a partial floor or shelf existed.

Pit 5

It was unclear at the time of excavation whether Pit 5 was a earlier pit or a part of Pit 3. Pit 3 had on both the eastern and western end narrow extensions that may comprise Pit 5. This pit's dimensions were 17 feet east-west and only 2.5 feet north-south. Yellow sandy silt, 1.2 feet thick, partially filled Pit 5 and was sealed by redeposited orange clay subsoil (1.6 feet thick). If this pit is not part of Pit 3, it was almost entirely destroyed by the construction of Pit 3. The western end of the pit was also intruded by Pit 1. No historic material was recovered from this feature.

Postholes Outside Structure

Three double-postmold postholes were uncovered near the southern building. While this construction technique was extremely uncommon, there are two seemingly-unrelated examples at the Museum site. A set of two of these postholes (CGER 6158A and 6159C) were located within three feet of the southern wall of the southern structure. The other double-molded posthole (CGER 6170B) was located well to the east of the same building.

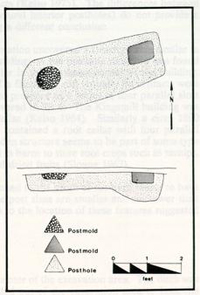

Figure 10. Postholes

Outside of Structure

Figure 10. Postholes

Outside of Structure

The holes to the south of the building measured 4.0 feet east-west and 1.4 feet north-south. Only 0.8 feet of the postholes survived the plow and erosion. The fill of the holes was a redeposited orange sandy clay subsoil. The postmold shapes were not consistent even within the same hole, but the size was consistent for all four postmolds. The shapes included circular, irregular, and rectangular. The molds measured 0.6 feet east-west and were extremely shallow. None of the molds extended to the bottom of the holes, suggesting that the holes were partially refilled before the post were set in place. The posts in each hole were placed 2.0 feet apart, and the distance between the nearest postmolds from each hole was 2.4 feet The fill of the molds was a brown sandy loam containing only a nail fragment and a pipe stem.

The double-molded posthole (CGER 6170B) located twenty-two feet from the east end of the southern building was slightly different from the others. It contained slightly smaller molds (0.5 feet) and a more irregular bottom. Like the other two double-molded postholes, the postmolds of CGER 6170B did not extend to the bottom of the hole. The shape of this hole was rectangular in plan, with two molds placed 2.0 apart. No artifacts were found and no function can be determined, though it appeared these holes were not structural in nature.

Function of Building

The same reasoning was used in assigning a function to the southern building as was used for the northern building. The structure's shape, the lack of a fireplace 29 or other domestic related features, and the lack of artifacts all lead to the conclusion that this building was a barn. Colonial barns normally did not house animal or farm tools, thus accounting for a lack of artifacts (Kelso 1975). The differences between the two buildings (i.e., pits and non-structural interior postholes) do not provide a persuasive enough argument for reaching a different conclusion.

The excavations at Kingsmill Plantation uncovered a structure very similar in plan and circumstance to the southern building. A ten posthole structure was found containing a four by twelve foot root cellar in the southeast corner of the building. This building also lacked any evidence of a fireplace, and virtually no artifacts were recovered. Even more interesting was the presence of a series of four parallel slots in the root cellar, identical to those uncovered in Pit 4. The Kingsmill building was also interpreted as a barn with a root cellar (Kelso 1984). Similarly a circa 1800 kitchen located in Cambell County also contained a root cellar with four parallel wooden beams (Graham 1981). The wooden structure seems to be part of some type of storage facility. Root cellars were used in barns to store root crops such as turnips, potatoes, and beets, as well as apples and dried fruits (Sloane 1967).

The double-molded postholes located to the south of the barn seems to have represented a non-structural activity. The post sizes are smaller and shallower than the structural postholes. That in addition to the location of these features suggested that they were not structural in nature.

The Boundary Ditch

A silted-in ditch ran through the center of the excavation area. The ditch was on a northwest-southeast axis and extended out of the excavation area to both the west and presumably to the south. Plowing had removed the top of the feature so that only 0.1 to 0.3 feet of fill had survived. The ditch silted in and was redug at least one time. The northern end of the feature shows clearly that it was excavated twice. At the western end, the ditch actually separates into two ditches. Plowing and erosion have completely destroyed this feature at the southern end of the site.

The ditch fill was a silted-in brown sandy loam with charcoal bits and oyster shell fragments where the ditch had intruded prehistoric pits. Some cow bones were recovered, but there were no dateable artifacts. This is not uncommon in boundary ditches, since their function is not related to any domestic activity. The presence of small water-worn pebbles and sand at the very bottom of the ditch shows that water once ran through this feature. Ditches were a common device used to divide different agricultural activities. Kelso (1971) and Smith (1986) also encountered boundary ditches during their excavations in Field 9. It is hard to tell without large-scale excavation if a complex network of boundary ditches existed, or if each time period has its own boundary markers.

Three small square postholes with postmolds were identified running parallel to the boundary ditch. The postholes were located five feet south of the ditch, with 30 the two northernmost holes spaced eight feet apart and the third located six feet from the center posthole. The holes were 0.8 feet across and 0.8 feet deep. The fill was a mixed brown sandy loam and redeposited orange sandy clay. The postmolds were small circular stains that appeared in the bottom of the postholes. These stains measured 0.3 feet across and contained a brown sand loam fill. No datable artifacts were recovered in any of the holes or molds. These postholes seem to represent a gate for a snake fence.

Snake fences leave very little archaeological evidence especially in areas disturbed by plowing. Noël Hume in Martin's Hundred describes these: "Some fences had no pre-dug post-holes, those made of wattles being woven around slender stakes that were simply pounded into the earth" (Noël Hume 1982). While the fence itself leaves little archaeological remains, a gate for the fence would have survived. The location of a gate slightly to the west of the two structures may signify that the barns are related to the features uncovered to the west of the current project by Barka in 1971.

The two barns and possibly the fence/boundary ditch made up part of a late 17th- or early 18th-century agricultural complex. The features uncovered by the College of William and Mary in 1971 just to the west of the project area are probably related to this complex. The presence of late 17th-century artifacts in these unidentified features indicate that historic activity in both areas date to the same time period. The features uncovered in 1971 may be part of the agricultural complex or may be a related domestic dwelling.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The decision to completely excavate the area impacted by the construction of the Martin's Hundred Museum turned out to be a good one based on the number and different types of settlements identified. While little evidence of either historic or prehistoric settlement was uncovered in the project area during previous archaeological surveys, complete excavation revealed the existence of four separate settlements located on the hill in Field 9. Although no Burwell graves were found, nor any part of Wolstenholme Towne uncovered in the project area, the site has added to the existing body of information about regional prehistoric and historic settlements. This excavation has demonstrated that the hill has been periodically occupied for the last 3000 years. While this occupation has never been very extensive, small groups of individuals have settled on this hill since the Archaic period.

Four groups of settlers have been identified through the series of small excavations conducted on and around the knoll. The earliest groups started using the terrace during the Archaic Period. The light scatter of datable artifacts from this time period suggests small short-lived encampments.

Following the Archaic settlement, several small groups apparently occupied the hill seasonally. The light density of features and Middle Woodland artifacts widely distributed over the entire hill implies repeated visits from a single or several small groups of individuals. The hill probably represented an ideal encampment for the harvesting of oysters and the exploitation of other resources, including river cobbles, available in the area. Recovery of the dog burial with the impressions of fabric offers a relatively unique opportunity to expand the knowledge of prehistoric textile-manufacturing processes.

The third occupation differed from its predecessors in two respects. The Late Woodland settlement was concentrated in a small area, and its intact shell midden and ossuary suggested a long-term occupation. The roasting pit provided two carbon dates for the Late Woodland occupation, but still does not establish whether the settlers of Martin's Hundred chose this land for settlement because it had previously been cleared by Native Americans or for some still unknown reason.

The historic component was made up of the remnants of an agricultural settlement with the possibility of a related domestic settlement existing to the west of the project area. These activities date to the late 17th or early 18th century. After this settlement the hill was used as a family cemetery for the Burwell family in the second half of the 18th century.

This project was designed to recover all material that was going to be disturbed by the construction of the Martin's Hundred Museum. The decision to excavate the project area completely turned out to be a necessary one in terms of archaeological remains. As with any construction project not all of the construction activities will be confined to the project area. Initially electric, phone, water, and 32 sewage lines must connect the building to the rest of the plantation. Later, supplementary construction activities such as tree and shrubbery planting, landscaping, walkways, and paths will be built, as well as additional outdoor lighting. All of these activities are destructive to the archaeological record. The question arises whether any of these activities will adversely affect the site enough to justify more excavation. The answer seems to be very possibly. If any of these activities occur to the west of the current project area, the results could be disastrous to the site. The unknown dimensions of two burial areas and the possibility of an extension of both the historic and prehistoric components makes any of these activities particularly risky. While there is less possibility of damage to an important part of the site, the nature of these sites does not preclude the possibility of damage done by construction activity outside of the current project area.

In order to limit the potential damage to the archaeological record complete excavation of the western part of knoll would be justified. While this sounds extreme, the alternative is a piecemeal destruction of the four settlements and the graveyard located on the hill. This could be avoided by first salvaging the area directly impacted by the museum construction. A small exhibition excavation could then excavate the areas threatened by secondary construction and could address points of interest such as defining the perimeter of the 18th century cemetery. This excavation could be used as an interpretive tool for visitors to the proposed museum. After visiting an archaeological museum, visitors should have a natural curiosity about the process of excavation. An exhibit dig would enrich the visitors museum experience by answering questions related to the process of excavation and archaeology in general, and would serve to tie together the 8000 years of occupation at Carter's Grove. This interpretive role in addition to saving the site on the hill from piecemeal destruction make fullscale excavation an attractive alternative.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1978

- Archaeology of George Washington Birthplace, Virginia. Southside Historical Sites Inc. Report of file, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1979

- 44JC118 and 44JC119: An Evaluation of Two Prehistoric Sites at Carter's Grove Plantation, James City County, Virginia. Report on file, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1986

- Toward a Resource Protection Process. Report on file, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1949

- Dogs of the Northeastern Woodland Indians. Massachusetts Archaeological Society Bulletin 10(2).

- 1964

- The Formative Cultures of the Carolina Piedmont. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 54(5).

- 1931

- "Seven Coastal Terraces in the Southeastem States." Washington Academy of Science Journal. Vol 21:503-513.

- 1986

- Late Woodland Cultures of the Middle Atlantic Region. University of Delaware Press, London.

- 1984

- Delaware Prehistoric Archaeology. University of Delaware Press, London.

- 1982

- Indian Ceramics From Coastal Plain Virginia. Archaeology of Eastern North America 10:95-117.

- 1940

- "Pleisticene Features of the Atlantic Coastal Plain." American Journal of Science. Vol. 238:757-787.

- 1981

- Green Hill Kitchen Drawing. Agricultural Buildings Project drawing on file, Department of Architectural Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 34

- 1883

- Barn Plans and Outbuildings. Orange Judd Company.

- 1972

- Geology of Yorktown, Poquoson West, and Poquoson East Quadangles. Charlottesville, Va. Division of Mineral Resources.

- 1971

- A Report on Exploratory Excavations at Carter's Grove Plantation, James City County, Virginia. Report on file at Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1975

- An Interim Report--Historical Archaeology at Kingsmill: The 1975 Season. Report on file, Department of Architectural Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1984

- Kingsmill Plantations, 1619-1800: Archaeology of Country Life in Colonial Virginia . Academic Press, Orlando.

- 1980

- Excavations at Carter's Grove Site H: June, 1979-January, 1980, Interim Report. Report on file, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1983

- The Prehistory of North Carolina: An Archaeological Symposium. University Graphics Inc.

- 1982

- Martin's Hundred. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

- 1973

- Post Miocene Statigraphy and Morphology, Southeastern Virginia. Charlottesville, Va. Comm. of Va. Division of Mineral Resources.

- 1967

- An Age of Barns. Ballentine Books.

- 1984

- The Hand Site Southampton County, Virginia. Archeological Society of Virginia, Special Publication No. 11.

- 1986

- Archaeological Testing of the Carter's Grove Museum Site. Report on file, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 35

- 1952

- Chickahominy: The Changing Culture of a Virginia Indian Community.

Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 96:157-225.

APPENDIX I. DESCRIPTION OF PREHISTORIC ARTIFACTS

Mary Ellen Hodges

37

The primary aim of the analysis of prehistoric artifacts recovered from excavation of the Carter's Grove museum site was to establish the chronological placement of cultural activities conducted within that portion of the plantation during the past. This end was accomplished through comparison of the formal characteristics of the artifacts to existing typologies for the Middle Atlantic Region. Examination of diagnostic artifacts indicated intermittent occupation from the late Early Archaic through Late Woodland Periods. As post-depositional disturbances had mixed the artifacts from these different components, little could be determined about functional or spatial variability in the use of the site by prehistoric peoples through time.

Ceramic Artifacts

Native American ceramics from the museum site excavation were analyzed to determine the cultural affiliation of Woodland Period occupations represented and to provide an estimate of the relative intensity of occupation through time in this portion of the Carter's Grove Plantation. After a preliminary sorting of the ceramic collection by size, each sherd with an exterior surface area of greater than 2 cm2 was examined to determine the type of temper used and the surface treatment applied to the exterior of the vessel. A total of 151 sherds from excavated contexts (including natural, prehistoric, and historic colonial features) was studied. No systematic attempt was made to count the number of vessels represented in the collection, since it was felt that this factor could not be reliably estimated through visual comparison of surface treatment techniques or wall and rim morphology. Mending of sherds from within the same excavation contexts was conducted, but the counts presented in this discussion represent the number of sherds present before mending. Analysis indicated that all sherds examined are tempered with crushed shell and are affiliated with either the late Middle Woodland Period or Late Woodland Period. Knotted net impressed and cord marked sherds in the collection are comparable to the Mockley series (Stephenson and Ferguson 1963: 105-109). The ware is common within most of the Virginia Coastal Plain, extending north into southern Delaware. Various radiocarbon dates from this region suggest a temporal placement from roughly AD. 200 to A.D. 900 (Egloff and Potter 1982: 103-104).

The Late Woodland Townsend series (Blaker 1963: 14-22) is represented in the collection by both fabric impressed sherds (Rappahannock Fabric Impressed) and sherds marked by incised decoration on a plain surface (Rappahannock Incised). The spatial distribution of Townsend ware within the Atlantic Coastal Plain generally mirrors that of the Mockley series (Egloff and Potter 1983: 107-109). Its temporal placement in Virginia is bracketed by radiocarbon dates of A.D. 945 (Outlaw 1978) and A.D. 1590 (MacCord 1965).

The few plain-surfaced sherds within the collection could not be assigned to 38 any cultural period given the small size of the fragments and the lack of significant stratigraphic relationships. While plain-surfaced vessels are considered a protohistoric type within the shell tempered ceramic tradition of the Virginia Coastal Plain (Egloff and Potter 1982: 112-114), Mockley ware vessels are sometimes smoothed directly below the rim. Vessel bases in both the Townsend and Mockley series are also commonly smoothed.

The frequency of each surface treatment in the collection is provided in Table 1. The figures in this table potentially present a misleading impression of the relative frequency of Mockley and Townsend vessels represented in the collection, however. It is reasonably certain that up to 73% of the Townsend series sherds originate from only one vessel, a Rappahannock Incised pot recovered from a large prehistoric hearth pit feature (CGER-6069A, 6069B, and 6069C). It is impossible to reliably estimate the number of vessels represented by the remainder of Townsend and Mockley sherds in the collection.

| Surface Treatment | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Knotted Net Impressed | 63 | 41.7 |

| Cord Marked | 4 | 2.6 |

| Fabric Impressed | 18 | 11.9 |

| Incised Decoration (over Plain) | 48 | 31.8 |

| Plain | 3 | 2.0 |

| Unidentified | 15 | 9.9 |

| Total | 151 | 99.9 |

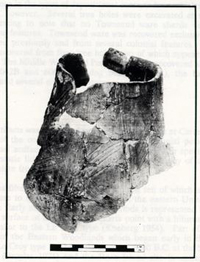

Because the Townsend ware vessel mentioned above is associated with two radiocarbon dates derived from charred wood in the hearth pit, it is worth describing the pot in further detail. Approximately one-third of the vessel was restorable. The 39 small jar has a constricted neck with the wall sloping outward from the rim to a very slight, rounded shoulder. The bottom of the jar is somewhat globular and appears to constrict to a subconoidal base. Although the mouth of the vessel is presently warped, the diameter of the orifice is approximately 9.5 cm in diameter. The exterior surface is smoothed and covered all over with incised decoration. The pattern of decoration consists of vertical bands of incised lines extending down from the rim. Filling the space between the bands are chevrons, composed of multiple incised lines, oriented along the vertical axis. Mends to this vessel were made from sherds recovered in all three excavated levels of the hearth feature, although the majority of sherds were recovered from the base of excavation unit 6069B. Radiocarbon dates derived from units 6069B and 6069C were, respectively, A.D. 1410 (540 +/- 90 BP, Beta-26119, radiocarbon halflife of 5568 years used) and A.D. 1280 (670 +/-70 BP, Beta-26120). This association is a significant addition to the data base needed for the investigation of temporal variability in Townsend ceramics as has been initiated in Delaware by Griffith (1980, 1982).

Townsend Vessel Recovered from Roasting Pit

Townsend Vessel Recovered from Roasting Pit

Examination of the distribution of ceramics within the site yielded little significant information. No significant differences were noted between the spatial distribution of Mockley and Townsend ware sherds (Figures 1 and 2). To a large degree, the distribution of ceramics from both wares simply mirrors the arrangement of excavated colonial features, from which approximately 30% of the ceramic collection was derived. Further, the only two prehistoric features, One Middle Woodland and one Late Woodland, to yield significant quantities of ceramics were located in adjacent ten foot excavation squares. Ceramics recovered from the hearth pit CGER-6069, Levels A-C constituted 85% of Townsend ceramics at the site and 44% of the total ceramic collection. Pit feature 6064A yielded 25% of the Mockley ceramics from the site and 12% of the total ceramic collection.

40There is some difference in the types of depositional contexts from which the ceramic sherds were derived, however. Several tree holes were excavated at the museum site and it is interesting to note that no Townsend ware sherds were recovered from the fill of these features. Townsend ware was recovered exclusively from the hearth pit mentioned previously and from several colonial features. In contrast, Mockley ware was recovered from four tree holes, two of which appear to have been intentionally filled. The Middle Woodland Period ware was recovered also from two prehistoric pits (6042B and 6064A), a dog burial (6032A), the Late Woodland Period hearth pit and several colonial features.

Lithic Artifacts

A total of 506 lithic artifacts was recovered from the Museum site at Carter's Grove. The vast majority of the collection was retrieved from colonial period deposits. Thus, most individual artifacts cannot be firmly associated with specific occupation periods. No diagnostic lithic artifacts were recovered from any of the intrusive features believed to date from the prehistoric period.

The collection includes fifteen projectile points or knives, ten of which are sufficiently complete to compare to types previously defined in the eastern United States. Occupation during the Early and Middle Archaic Periods is represented by two points recovered from the surface of the site. One quartz point with a bifurcate base and serrated blade is similar to the Le Croy type (Kneberg 1954). Part of a larger bifurcate tradition within the Eastern Woodlands which began early in the seventh millennium B.C., the Le Croy type has been dated to ca. 6300 B.C. at the St. Albans site in West Virginia (Broyles 1971) and the Rose Island site in eastern Tennessee (Chapman 1975). Another quartz point, characterized by a rather narrow, serrated blade and a contracted stem descending from pronounced shoulders, is similar to the Morrow Mountain H type suggested to date ca. 4000-3000 B.C. (Coe 1964).

Two types of projectile points identified in the collection are likely to have originated from the same occupation(s) responsible for the Mockley ceramic assemblage. Six points are referable to the Rossville type (Ritchie 1971; Stephenson and Ferguson 1963), a medium-sized point with a contracting stem. Radiocarbon dates from the northeastern United States compiled by Gleech (1985) suggest the type was is use from ca. 500 B.C. to A.D. 400. Points in the Carter's Grove collection attributed to the Rossville type are quite variable in size as indicated in Table 2. Shoulder and stem morphology also varies, with some stems contracting directly from the shoulder and some inset slightly so that the shoulder is more pronounced. The points were produced from both quartzite and jasper. Both jasper points appear to have been fire-altered before flaking. The greater thickness of these two points relative to those of quartzite represents problems in thinning the interior of the blade.

41  Figure 11.

Examples of Projectile Points

Figure 11.

Examples of Projectile Points

| Provenience | Material | Length* | Width* | Maximum Thickness* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface | quartzite | n.a. | 2.13 | 0.63 |

| CGER-6058A | quartzite | 3.08 | 2.43 | 0.78 |

| CGER-6058A | jasper | n.a. | 2.11 | 0.99 |

| CGER-6163H | jasper | n.a. | 2.54+ | 1.22 |

| CGER-6164D | quartzite | 3.64 | 1.98 | 0.72 |

| CGER-6174B | quartzite | n.a. | 1.85+ | 0.43 |

Also probably dating from the Middle Woodland Period is a medium-sized side-notched point of quartz recovered from the surface. This point is similar to the Potts Side-Notched variety defined at the Croaker Landing site in James City County, Virginia. Ceramic associations at that site suggest a date of ca. 100 B.C. to A.D. 400 for the type (Egloff et. al. 1988).

The remaining points in the Carter's Grove collection are too fragmentary for positive identification. One possible triangular preform and a base to what is probably a triangular point each of quartz, were recovered. Four additional quartz point fragments, two tips and two bases, were also retrieved. The collection also includes a medium-sized stemmed point of quartzite, probably dating from the Late Archaic/Transitional Period. Grinding along all edges of the point, including the distal edges of the snapped blade, suggests that the artifact may have been secondarily deposited at the site from an intertidal context.

The remaining lithic artifacts in the Carters Grove collection will be described only briefly, since disturbances to the prehistoric components have precluded the determination of the cultural affiliation of less diagnostic types. In addition to the projectile points described above, the collection includes eleven bifaces, eight quartzite and three quartz. Several of these bifaces are derived from large decortication flakes or fragments of cobbles split through bipolar percussion.

Eleven modified flakes, nine quartzite and two jasper, were identifîed in the collection, including what appear to be side and end scrapers. Ground stone tools 43 consisted of one large cobble anvil stone of quartzite with a pecked surface on one face and two battered quartzite cobbles which may have been used as hammerstones.

Also included in the collection are nine cores (five quartz, 2 quartzite, and 2 jasper) and 438 fragments of debitage including flakes and shatter. As indicated in Table 3, the majority of debitage was of quartzite. Quartz and jasper contributed, respectively, roughly thirty-two and eight percent of the assemblage. A general assessment of the debitage was provided by measuring the fragments against grids in five size categories and by noting the presence or absence of cortical surfaces (Tables 4). The collection appears to display a rather high frequency of cortical surfaces considering the small size of the flakes. This discrepancy may be due to the use of small cobbles. The higher frequency of cortical surfaces for quartz and jasper debitage in the smaller size ranges suggests these materials were only available in smaller packages than quartzite.

| Quartzite | Quartz | Jasper | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Debitage Without Cortex | 211 | 79.6 | 104 | 74.8 | 23 | 67.6 |

| Debitage With Cortex | 54 | 20.4 | 35 | 25.2 | 11 | 32.4 |

| Total | 265 | 139 | 34 |

| Size Category | Quartzite (%) | Quartz (%) | Jasper (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 10 mm2 | 5.2 | 7.7 | 4.3 |

| 10-20 mm2 | 61.6 | 67.3 | 82.6 |

| 20-30 mm2 | 22.3 | 16.3 | 13.0 |

| 30-40 mm2 | 5.7 | 4.8 | -- |

| 40-50 mm2 | 3.8 | 2.9 | -- |

| 50-60 mm2 | 1.4 | 1.0 | -- |

| Size Category | Quartzite (%) | Quartz (%) | Jasper (% |

| < 10 mm2 | -- | -- | 9.1 |

| 10-20 mm2 | 31.5 | 51.4 | 72.7 |

| 20-30 mm2 | 37.0 | 31.4 | 18.2 |

| 30-40 mm2 | 20.4 | 11.4 | -- |

| 40-50 mm2 | 7.4 | 2.9 | -- |

| >50 mm2 | 3.7 | 2.9 | -- |